Martin, Matthiessen & Painter (2010: 166):

Like a clause, a nominal group embodies all three metafunctions.

Experientially a nominal group construes a participant – a conscious being (human or animal), an animal not treated as conscious, an institution, a discrete object, a substance, or an abstraction. The group provides the resources for construing a participant as a thing located somewhere in a taxonomy of things expanded by a range of different qualities.

Interpersonally, a nominal group enacts a person – a role defined by reference to the interaction as either an interactant (‘first/second person’) or a non-interactant (‘third person’) and it can be expanded by various interpersonal assessments.

Textually, a nominal group presents a discourse referent – a participant and person created as part of a message with status as recoverable (identifiable) to the addressee (e.g. that bird) or as non-recoverable (non-identifiable) at a given point in the discourse (e.g. a bird).

Blogger Comments:

[1] This is misleading. A clause embodies all three metafunctions in the systems and structures of the clause. So, like a clause, a nominal group embodies all three metafunctions in the systems and structures of the nominal group. (See the following post.)

However, the authors do not address the question of how all three metafunctions are embodied in the systems and structures of the nominal group. Instead, they focus on the semantics that the nominal group, as a unit, realises.

[2] To be clear, this is the semantics of 'participant', the ideational element that the nominal group realises. That is, the focus is on semantics, not grammar.

[3] To be clear, this is the semantics of a proposed interpersonal element that the nominal group is proposed to realise. That is, the focus again is on semantics, not grammar. But consider the so-called 'persons' enacted in:

[4] To be clear, this is the semantics of a proposed textual element that the nominal group is proposed to realise. That is, the focus again is on semantics, not grammar. But consider the so-called 'referents' presented in:

Most importantly, neither that bird nor a bird is a referent unless referred to elsewhere in a text. That is, the authors mistake a nominal group with a reference item (that bird) — or without (a bird) — for a referent. Moreover, the authors mistake the recoverable identity signalled by the reference item (that) for the identifiability (of the Thing) of the nominal group featuring the reference item (that bird).

These types of misunderstandings of cohesive reference can be found in Martin (1992), Matthiessen (1995), and the two editions of IFG edited by Matthiessen (2004, 2014). For a a self-consistent exposition of reference, see the original model in Halliday & Hasan (1976), Halliday (1985) and Halliday (1994).

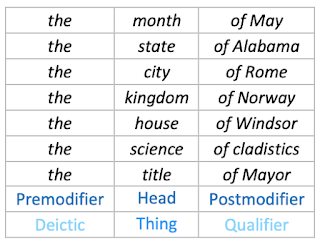

.png)

.png)